- Home

- Carlos Ruiz Zafón

The City of Mist Page 3

The City of Mist Read online

Page 3

Translated by Lucia Graves

Laia was five years old the first time her father sold her. It was an innocent, kind-hearted arrangement, with no malice other than that inspired by hunger and pressing debts. Eduardo Sentís, a hapless, penniless portrait photographer, had just inherited the studio of the man who had been his mentor and boss for over twenty years. He had started work there as an unpaid trainee, had then become an assistant and finally, after obtaining the required qualifications, though not the salary, had moved on to become photographer and junior manager. The studio’s premises occupied a spacious ground floor on Calle Consejo de Ciento and consisted of four sets, two developing rooms and a storage room bursting with out-of-date equipment in a dilapidated state. Aside from the studio, Eduardo had also inherited the numerous unpaid bills left by his boss, who had been more of a man of lenses and plates than one of clarity in his accounts. At the time of his boss’s demise, Eduardo Sentís had not received his wages for over six months. In the words of the executor, the post-mortem takeover of the business and the miserable inheritance that came with it were supposed to be a just reward for his loyal and austere dedication. But as soon as light and accountants fell on the company’s business books, Eduardo Sentís realised that what his boss had left him in return for having offered him his youth and his efforts was no inheritance but a simple curse. He had to fire all the employees and confront the survival of the studio, and his own survival, alone. Until then, a large part of the business generated by the studio focused on family celebrations of various kinds, from weddings and christenings to funerals and Holy Communions. Work related to funeral parlours and burials were a speciality of the house, and over time Eduardo Sentís had found it easier to light and photograph the deceased than the living. The dead never looked out of focus in long exposures because they didn’t move or have to hold their breath.

It was his reputation as a photographer of bereavement that secured him a job which, at first sight, seemed straightforward and uncomplicated. Margarita Pons, the five-year-old daughter of a wealthy married couple with a mansion on Avenida del Tibidabo and an industrial estate on the banks of the River Ter, had died from some strange fever on New Year’s day of 1901. Her mother, Doña Eulalia, had suffered a nervous breakdown which the family doctors had hastened to mitigate with generous doses of laudanum. Don Federico Pons, paterfamilias and a gentleman with no room or time for sentimentalities, who had seen more than one of his children die, did not shed a tear or utter a groan. He already had a healthy and talented first-born heir. The loss of a daughter, for all its sadness, also meant an obvious saving in family expenditure, both long- and medium-term. What Don Federico wanted was to hold the funeral service without delay, followed by the burial in the family vault in Montjuïc Cemetery, so that he could resume his daily work routine as soon as possible. But Doña Eulalia, a fragile creature who was prone to the influence of the sinister ladies of The Light, a spiritualist society on Calle Elisabets, was in no fit state to turn the page as resolutely as her husband. In order to silence her sighs, Don Federico allowed her to have a series of photographs taken of the deceased princess before the undertakers proceeded with the body’s eternal consignment to an ivory coffin adorned with pieces of blue glass.

Eduardo Sentís, photographer of the dead, was summoned to the Pons family mansion on Avenida del Tibidabo. The property lay hidden inside a dense grove accessed through a wrought-iron gate on the corner of the avenue and Calle José Garí. It was a grey, grim day, a sliver of that harsh, misty winter that had brought such bad luck on poor Sentís. As he didn’t have anyone with whom to leave his daughter Laia, he took her with him. Holding the girl with one hand and his lens- and-bellows case in the other, Sentís took the blue tram and turned up at the mansion, determined to start the year with some hard cash income. He was welcomed by a servant who led him through the garden to the house, where he was shown to a small waiting room. Laia was fascinated by everything she saw, because she’d never seen a place like that. It looked like something straight out of a fairy tale, but one of those about an evil stepmother and mirrors that were poisoned by bad memories. Glass chandeliers hung from the ceiling, statues and paintings lined the walls and thick Persian carpets covered the floors. As he gazed at all that weighty fortune, Sentís was tempted to put up his price. He was received by Don Federico, who barely looked at him and addressed him in the tone he reserved for servants and factory workers. He was given an hour to take a set of photographs of the deceased child. When he saw Laia, Don Federico frowned disapprovingly. It was a widely accepted dogma among the males of his family that the utility of the female gender was confined to the bedroom, the table or the kitchen, and that brat had neither the age nor the pedigree to be considered for any of the three. Sentís excused the child’s presence claiming that the urgency of the job had not given him enough time to find someone to take care of her. Don Federico sighed unsympathetically and told the photographer to follow him up the stairs.

The little princess had been placed in a room on the first floor. She lay on a wide bed covered in white lilies, her hands crossed over her chest and clutching a crucifix. A tiara of flowers adorned her forehead and she wore a diaphanous silk dress. Two silent male servants guarded the door. A shaft of ashen light from the window fell on the child’s face. Her skin, almost transparent, had taken on the colour and appearance of marble, with blue and black veins running through it. Her eyes had sunk into their sockets and her lips were purple. The room stank of dead flowers.

Sentís told Laia to wait in the corridor and began setting up his tripod and camera in front of the bed. He thought he’d create six plates in all. Two close-ups with one of the long lenses, two mid-range shots from the waist up and a couple of general, full-body shots. All from the same angle, because he suspected that a profile or a three-quarter shot would draw attention to the web of veins and dark capillaries under the girl’s skin and produce pictures that might look more sinister than the situation required. A slight overexposure would whiten the skin and soften the image, giving a warmer, more diffuse aura to the body and a greater depth of field and detail to the surrounding area. While he prepared the lenses he noticed something moving at the far end of the room. What he had thought was yet another statue when he came in turned out to be a woman in black with her face covered by a veil. It was Doña Eulalia, the princess’s mother, who was sobbing quietly as she crept around the room like a lost soul. She approached the dead girl and stroked her cheek.

‘My angel speaks to me,’ she told Sentís. ‘Can’t you hear her?’

Sentís nodded and continued with his preparations. The sooner he got out of there, the better. When he was ready to start taking the first images, the photographer asked the mother to move out of the camera’s field of vision for a few moments. She kissed the corpse on the forehead and stood behind the camera.

Sentís was concentrating so hard on his task he hadn’t noticed that Laia had stepped into the room and was standing next to him, petrified, staring at the dead girl laid out on the bed. Before he was able to react, Señora Pons walked over to Laia and knelt down in front of her. ‘Hello, sweetheart,’ she said. ‘Are you my angel?’ The lady of the house took Sentís’s daughter in her arms and pressed her against her chest. Sentís felt his blood freeze. The mother of the deceased child was singing a lullaby to Laia as she rocked her in her arms, telling her that she was her angel and they would never again be parted. At that moment Don Federico appeared. He pulled the girl from his wife’s arms and led Doña Eulalia out of the room, while she begged to be left with her angel, her arms extended towards Laia. As soon as they were left alone, the photographer exposed the plates as fast as he could and put away his equipment. On his way out, Don Federico was waiting for him in the entrance hall, holding the payment for his services in an envelope. Sentís noticed that the envelope contained twice the amount they had agreed upon. Don Federico was looking at him with a mixture of hope and disdain. He made him an offer then and there: in exchange for a generous sum of money the photographer would bring his daughter to the mansion the following day and leave her there until the evening. Stupefied, Sentís looked at his daughter and then at Pons. The industrialist doubled the amount he’d offered. Sentís silently shook his head. ‘Think about it,’ was all Pons said when he bid him goodbye.

The photographer spent a sleepless night. Laia found him crying in the pale light of the studio and held his hand. She told him to take her to that house: she would be the angel and would play with the lady. By mid-morning they were both standing outside the mansion’s gates. Sentís was handed the money by a servant and told to return at seven o’clock in the evening. He saw Laia disappear inside the large house and he dragged himself down the avenue until he found a café at the top of Calle Balmes where they served him a glass of brandy, and then another, and a further one, and as many as were necessary until it was time for him to go and pick up his daughter.

Laia spent that day playing with Doña Eulalia and the dolls that had belonged to the deceased. Doña Eulalia dressed her in the dead girl’s clothes, kissed her and held her in her arms, telling her stories and talking to her about the girl’s brothers, about her aunt, about a cat they’d once had but had run away. They played hide-and-seek and went up to the attic. They ran around the garden and had a snack by the fountain, throwing breadcrumbs to the coloured fish that darted through the water of the pond. At sunset, Doña Eulalia lay down on her bed with Laia by her side and drank her glass of water with laudanum. And so, embracing in the dark, the two fell asleep until one of the male servants woke Laia up and took her to the front door where her father was waiting, his eyes reddened with shame. When he saw her he fell on his knees and hugged her. The servant handed him an envelope with the

money and instructed him to bring his daughter back the following day at the same time.

Every day of that week Laia went to the mansion to become the little angel, to play with her toys and wear her clothes, to answer to her name and disappear into the shadow of the dead girl who haunted every corner of that dark, sad house. By the sixth day, Laia’s memories were those of little Margarita, and her past existence had evaporated. She had become that longed-for presence and had learned to embody it with more intensity than the deceased herself. She had learned to interpret looks and longings, to hear the trembling of hearts broken with loss and find the gestures and the touch that consoled the inconsolable. Without realising, she’d learned to become another person, to be nothing and nobody, to live in the skin of others. She never asked her father not to take her to that place, nor did she tell him what happened during the long hours she spent inside. The photographer, intoxicated with money and relief, salved his conscience by telling himself that this was an act of charity and Christian piety. ‘If you don’t want to, you don’t have to go to that house any more, do you hear me?’ her father would say every night when they came back from the mansion. ‘But we’re doing a good deed.’

The little angel disappeared on the seventh day. They said that Doña Eulalia had woken up at dawn and when she didn’t find the girl next to her she had begun searching frantically for her all over the house, thinking they were still playing hide-and-seek. The laudanum and the darkness led her to the garden where she thought she heard a voice and then thought she could see a little angel – its face lined with blue veins, its lips black with poison – looking at her from the depths of the pond, calling her, inviting her to submerge herself and accept the frozen, silent embrace of the shadow that was pulling at her and whispering: ‘Mother, now we’ll always be together, just as you wanted.’

For years the photographer and his daughter travelled to every city and town in the country with their circus act of deceptions and pleasures. By the time she was seventeen Laia had learned to embody lives and faces aided by a few sheets of paper, an old photograph, a forgotten story or a handful of memories that refused to die. Sometimes her art served to bring back the longing of a first secret and forbidden love, and her trembling body would awaken beneath the hands of older lovers, individuals who had been able to buy everything in life except what they most desired and had allowed to slip away.

Businessmen endowed with too much money and too little life would imagine themselves, perhaps for only a few minutes, in bed with women whom the girl had conjured up from a secret longing, from the pages of a diary or a family portrait – and whose memory would stay with them the rest of their lives. Sometimes the miracle of her artistry achieved such perfection that the client forgot it was all a fantasy with which to cloud his senses and poison them with pleasure for a few moments. The client then believed the young girl was who she was pretending to be, that the object of his desire had come alive, and he did not want to let it go. He was prepared to lose his fortune or the empty, barren life he’d lugged behind him until then in order to live the rest of his dream in the arms of that girl who could become what one most desired.

When this happened – and it had been happening more and more frequently because Laia had learned to read the souls and the desires of men with such precision that even her father sometimes felt the game had gone too far – they would both run away like fugitives at dawn and hide in another city, in other streets, for weeks on end. Then Laia would spend the day hidden in the suite of a luxury hotel, sleeping most of the day, buried in a lethargy of silence and sadness, while her father did the rounds of the city’s casinos and lost, in just a few days, the fortune they had accrued. Her father’s promises of abandoning that life would be broken again: he would hug her and whisper that there would only be one more time, one more client, and then they would retire to a house by a lake where Laia would never again have to give life to the hidden desires of some wealthy gentleman sick with loneliness. Laia knew that her father lied without realising he was lying, as all great liars do who first lie to themselves and are then unable to see the truth even if it’s stabbing them in their hearts. She knew he was lying and she forgave him because she loved him and because, deep down, she wanted the game to continue, she wanted to find another character whose life she could awaken and with whom she could fill, for a few hours at least, that huge void that was growing inside her and was eating her alive at night as she waited, between silk sheets, in the suite of a luxury hotel, for her father to return, inebriated with liquor and failure.

Once a month Laia received the visit of an older man wearing a dejected expression, whom her father liked to call Doctor Sentís. The doctor, a fragile person who tried to hide a look of despair and defeat behind his glasses, had seen better days. When he was young, in more affluent times, Doctor Sentís had owned a prestigious surgery on Calle Ausias March, visited by damsels of a marriageable age and dames who were more prone to reminisce. In that surgery, legs open and spread out in the blue-ceilinged room, the cream of Barcelona’s bourgeoisie had no secrets or modesty before the kind doctor. His hands had delivered hundreds of children from wealthy homes and his care and advice had saved the lives and often the reputation of patients who had been deliberately kept ignorant about an important part of their bodies, the part that most burned and throbbed, so that it held more secrets for them than the mystery of the Holy Trinity.

Doctor Sentís had the quiet manners and the friendly and reassuring disposition of someone who sees no shame or embarrassment in the facts of life. Calm and affable, he knew how to gain the trust and appreciation of women and young girls, once terrorised by nuns and friars who only touched their private parts in the dark and at the devil’s bidding. He would explain, with no awkwardness or fuss of any sort, how their bodies worked, and taught them not to feel bashful about what, according to him, was only the work of God. Naturally, a talented, successful man who was also decent and honest could not last long in good society, and sooner rather than later, his moment came. The fall of the righteous is always brought about by people who are most indebted to them. One doesn’t betray those who want to ruin us but those who offer us a hand, even if only because we don’t wish to acknowledge the debt of gratitude we owe them.

In the case of Doctor Sentís, betrayal had been in the offing for some time. For years the kind doctor had attended a lady of noble pedigree who journeyed through a marriage – lacking in contact and even words – to a man she barely knew and with whom she had shared a bed twice in twenty years. Out of habit, the lady had learned to live with cobwebs round her heart, but she refused to smother the fire between her legs, and in a city where so many gentlemen liked to treat their own wives as saints and virgins, and those of others as sluts and whores, it was easy enough for her to find lovers and fleeting devotees with whom to kill the tedium and remind herself that she was still alive, even if only from the neck down. Adventures and misadventures in others’ beds carried their risks and the lady kept no secrets from the good doctor, who made sure that her pale, longing thighs did not fall prey to diseases and disreputable ailments. The doctor’s potions, ointments and wise advice had kept the lady in a state of immaculate ardour for years.

As life would have it – and it usually does, given a chance – the doctor’s good turns were repaid with bile and spite. Any city’s polite society is a world as small as its reserves of honesty, and it was a foregone conclusion that the accursed day would come when one of those half-hour lovers, out of meanness or spite, or better still, out of self-interest, would reveal the secret and passionate life of a sad and lonely woman to the sharp eyes of her companions in jealousy. The story of the whore in silk stockings, a nickname with which some gossip-monger with literary pretensions christened her, spread like wildfire among the chattering members of a community that thrived on slander and suspicions.

Distinguished gentlemen guffawed as they described, in spiteful detail, the charms of the lady-turned-whore in silk stockings, and their no less distinguished and disdained wives spoke under their breath about how that fallen hooker, who had once been considered their friend, had performed unmentionable acts and corrupted the souls and the nether regions of their husbands and sons on all fours and with her mouth full, performing linguistic acrobatics they hadn’t learned in their eleven years at the School of the Sacred Heart. The story, which was on everyone’s lips and had grown increasingly outlandish, did not take long to reach the august husband of the so-called whore in silk stockings. Later, people said that nobody was to blame, that it was the lady’s own decision to leave the family home, abandon her clothes and jewels and move into a cold apartment on Calle Mallorca, a place with no light and no furniture. And there, one January day, she lay down on the bed facing an open window and drank half a glassful of laudanum, until her heart stopped and her eyes, open to the icy wind of winter, shattered in the frost.

The Prisoner of Heaven

The Prisoner of Heaven The Shadow of the Wind

The Shadow of the Wind Marina

Marina The Angel's Game

The Angel's Game The Midnight Palace

The Midnight Palace The Prince of Mist

The Prince of Mist The Prisoner of Heaven: A Novel

The Prisoner of Heaven: A Novel The Labyrinth of the Spirits

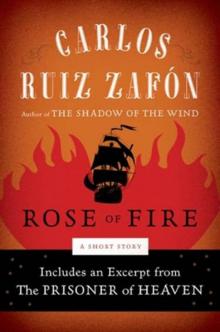

The Labyrinth of the Spirits Rose of Fire

Rose of Fire